REActing to COVID-19: why responding to rights violations is more important than ever

2017 Gemma Taylor for Frontline AIDS

2017 Gemma Taylor for Frontline AIDS

Many marginalised communities are using Frontline AIDS’ Rights – Evidence – ACTion (REAct) tool to monitor and respond to the daily human rights violations people experience.

Oratile Moseki, Human Rights technical lead, and Monika Sigrist, Senior Advisor for Human Rights Data Systems, explain why REAct has become more important than ever in the COVID-19 era.

What is REAct?

Monika: REAct was developed with, and for, civil society organisations. It enables them to systematically document human rights violations being experienced by people in their communities and refer people to health, legal and other public services. The more REAct is used, the more data on rights-violations it generates, which can then inform human rights-based HIV programming, policy and advocacy.

An increasing number of countries involved in the Partnership to Inspire, Transform and Connect the HIV response (PITCH) are using REAct. Their adoption is timely as we see how the COVID-19 crisis is increasing rights violations in many of these countries, particularly for those in marginalised groups.

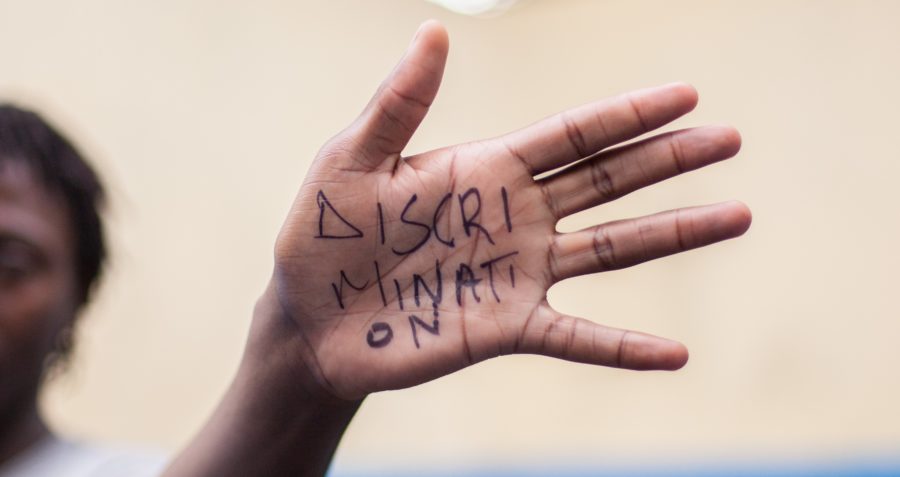

What kinds of rights violations are increasing?

Oratile: What stands out for me is the unjustifiable behaviour of state actors. Police, military, even in some instances healthcare and social service workers, are using COVID-19 restrictions to repress marginalised communities through violence, harassment and unlawful arrests. These actions are politically driven and stigmatising and go far beyond reasonable limitations to people’s rights to control COVID-19.

Monika: We’re also seeing pre-existing inequalities exacerbated. Experiences of violence from partners, family members and the general community are increasing for marginalised people, for instance. And stigma is ever present – we’ve had cases where people from marginalised groups are being blamed for spreading COVID.

Any examples that particularly stand out?

Oratile: In Uganda, a group of young gay men were rounded up by the police on the grounds they were spreading COVID-19. They were marched through the streets, unlawfully arrested, detained and denied legal representation. Initially the state wouldn’t bring them to court as COVID restrictions meant all hearings were stopped. Although this wasn’t documented through REAct it’s a chilling example of the type of intentional violations and unintentional rights implications arising from the current situation.

Has REAct become more necessary than ever?

Oratile: Yes. Community-led action has been critical to responding to COVID-19 – as it was with HIV in the early days of the epidemic – and we need to use and adapt what we’ve learnt in responding to HIV to more effectively respond to COVID-19.

Now more than ever, our communities are relying on civil society organisations to support them and to provide services and referrals, and that makes REAct that much more important. And these violations now include more basic needs. For instance, people are struggling to access antiretrovirals, even food, housing and shelter. All this has created a bigger burden on civil society organisations – if they don’t do it then it’s not going to get done.

With REAct we can get ahead of the threats. It helps community organisations see trends and act quickly, preventing further human rights violations, then use the data to show what needs to change in the way the state is responding.

How is REAct working with PITCH partners during COVID-19?

Monika: We’ve recently held virtual training workshops for Uganda PITCH partners. One of these was with organisations working with adolescent girls and young women, who are completely new to REAct in Uganda.

Budget was provided to ensure people had enough airtime to participate. We also pre-recorded videos around key learning points so those struggling with connectivity could download the videos afterwards. This happened in May and they have just gone live with using REAct so it shows that it’s possible to go from virtual training to implementation.

Have COVID restrictions led to practical barriers for REActors? And have ways around these issues been found?

Monika: REAct works on the basis of meeting people – interacting with them, getting their stories. So initially organisations were struggling to reach current and new REAct clients, despite the ever-growing need.

Some organisations have set up hotlines, promoted on social media, which people can ring to report violations, which is helping to tackle the issue of REActors not being out in communities. In contexts where there are curfews people are able to move freely before a certain time, so REActors are wearing protective equipment and meeting people in person.

When you’re asking someone about a human rights violation, you need to establish a friendly rapport, which is sometimes hard to do over the phone. So people are trying out different platforms to find the one that works best – for instance, video calling as opposed to instant messaging or phone calls.

These strategies are working; cases continue to come in. The REActors are still finding ways to reach the people who need them.

Have the needs of REActors changed due to COVID-19?

Oratile: In many ways. There are simple things, such as the need for bicycles to help REActors move around safely, and for airtime for them and their clients – without this, how do people report in the first place?

How does REAct support advocacy in PITCH countries?

Monika: PITCH partners in Kenya and Mozambique have been using REAct for around six months now so they should soon be in a position to use the data they have been collecting to build evidence for advocacy purposes. We are planning to hold a virtual event to look at what the data is telling them and discuss how they can use it.

Oratile: We are hearing that REActor organisations in Kenya are trying to bring in other organisations that might not be doing REAct implementation. There’s a sense that this evidence could be a gift to the network of partners who work on advocacy there. It will be wonderful to see this process unfold – and with it the sense that REAct data is not just useful for the organisation collecting it, but the community as a whole.

Tags

Human rightsREAct