Kenya: Funding cuts risk pushing HIV response underground

Funding cuts are unraveling Kenya’s HIV response and driving infections underground - but communities are determined to keep essential services alive.

For nearly two decades, Kenya was considered one of Africa’s HIV success stories – a country where new infections had been steadily declining, prevention programmes were expanding, and community-led innovations were helping close long-standing gaps in access. But the sudden withdrawal of US funding in 2024–25 has sent shockwaves through the HIV response, exposing deep vulnerabilities that had been masked by years of donor support.

Kenya now finds itself at a critical moment. New infections are rising for the first time in years, key populations have been pushed out of safe spaces and into unprepared clinics, and – perhaps the most alarming development – the epidemic is becoming statistically invisible as thousands of those most at risk of HIV fear disclosing who they are.

The cuts have deeply impacted the global HIV response. Half of Frontline AIDS’ 54 global partners (27) have been impacted by the foreign aid cuts, with some partners losing up to 90% of their funding.

In Kenya, national data tells a stark story: new HIV infections jumped from 16,752 to 20,105 in one single year (Source: NSDCC), reversing a downward trend and signalling the early stages of a possible resurgence. New reporting from Frontline AIDS’ Transition Initiative – which empowers communities and civil society to shape the transition of HIV services in the wake of the cuts – warns that without immediate action, this upward trajectory could accelerate sharply in the years ahead.

The collapse of prevention

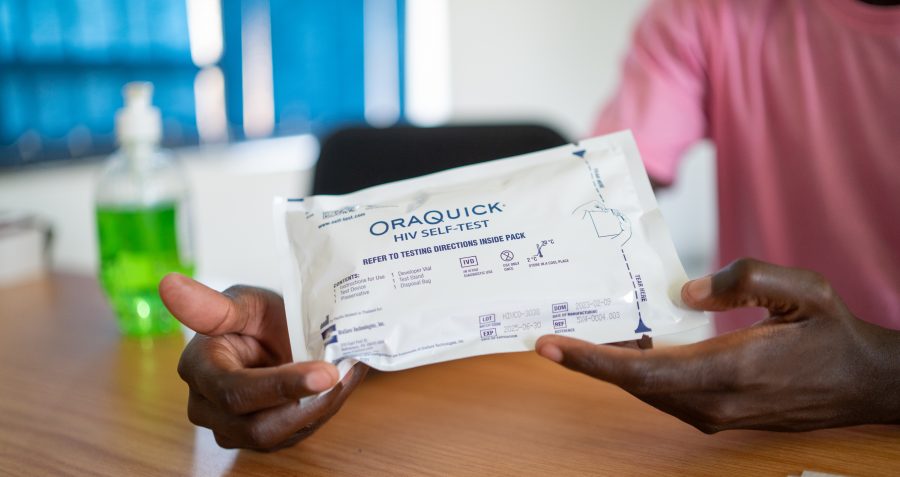

Few areas have been hit harder than HIV prevention. Patriciah Jeckonia of LVCT Health – one of Kenya’s leading civil-society organisations providing community HIV services – describes the shift plainly: “We’ve seen a huge drop in uptake of products like PrEP… it has gone down drastically and it’s a matter of concern for us.”

The data bears this out. Between early 2024 and early 2025, the number of people newly accessing oral PrEP dropped by nearly half. During the same period, the DREAMS programme for adolescent girls and young women has been closed, and hundreds of thousands of people from key populations have lost access to targeted prevention services.

Drop-in centres – vital safe spaces designed specifically for groups facing severe stigma – have closed across the country. And because condoms are no longer reliably available through community-led channels, many people now go without. The result is a sharp and immediate erosion of gains that took years to build. Solo, who is part of a key population in Kenya said: “We are worried about the chronic stock-out of condoms and lubricants that are critical for preventing HIV and sexually transmitted infections, especially among key populations.”

Part of the shift is political. Prevention was once a well-funded priority, and government buy-in followed donor investment. When that funding disappeared, so too did that focus. As Patriciah puts it: “[Kenya] bought into the donors’ prevention agenda because it was well financed. When donors said prevention is no longer a priority, it was very easy for the country to drop it. Investment in HIV prevention programming is still a concern.”

For adolescent girls, LGBTQ+ people, sex workers and people who use drugs, the consequences have been rapid and profound – not only reduced access to prevention tools, but a return to the conditions that heighten their risk of HIV transmission.

A rapid shift into clinics that weren’t ready

As funds dried up, the message from government and health facilities was blunt: all services should be integrated into public clinics. “It was integrate, integrate, integrate,” Patriciah explains. “Providers had not been prepared or sensitised to offer key-population-friendly or youth-friendly services.”

The consequences have been predictable. Public-facility staff, untrained in community-led approaches, suddenly found themselves seeing clients they had never encountered before. “There have been struggles in terms of confidentiality,” Patriciah says. “Some providers were even shocked, saying ‘wow, it’s actually a reality – we have key populations in our country’. And those kinds of comments can really put one off.”

Long queues, stigma, and breaches of privacy have pushed many people away from services altogether, with LGBTQ+ people and sex workers reporting hostility within clinics. The shrinking of safe spaces has left people with nowhere to go but to facilities that are often unprepared – or unsafe – for them.

An epidemic going underground

One of the most troubling trends is that key populations are still accessing some health services, but are no longer disclosing aspects of their identities that increase their risk of HIV. “Most of us are not disclosing that we are KPs,” says Solo.

This shift has far-reaching consequences. When people stop disclosing, the epidemic becomes harder to see. Groups most vulnerable to HIV risk are increasingly counted within ‘general population’ data, masking the true picture of transmission. “We’re going to lose data,” Patriciah warns. “If you want to programme for key populations using the national data, that’s going to be a challenge. We have to think about how to create a safe space for KPs to feel safe to declare.”

This comes at a time when other essential data systems, including Kenya’s electronic medical records platform and the Integrated Bio-Behavioural Survey, have been disrupted or delayed. The combined effect is a system trying to manage a rising epidemic with incomplete information – a dangerous position for a country with Kenya’s HIV burden.

Adding to the uncertainty is a wider political hesitation. While civil society pushes for domestic sustainability, parts of government remain hopeful that US funding may be restored. That hope, Patriciah suggests, has slowed momentum towards developing a long-term national plan. “Some in government have talked positively about how the money is going to come back,” she says. “It’s very confusing. Just when we were gaining traction on domestic financing, it takes us back.”

Fragile but determined resilience

And yet, despite the disruption, one theme comes through clearly in both testimony and community monitoring: people are not giving up.

Communities are creative and solution-driven people. We will figure this out.

Across Kenya, adolescent girls are organising improvised support networks in the absence of DREAMS. Community groups are working out how to navigate public clinics more safely. Civil-society organisations are lobbying for essential lab tests to be covered under the new Social Health Insurance Fund. Community health promoters are stepping in where peer educators once were, keeping some continuity of support alive despite the funding vacuum.

This resilience is not a substitute for well-funded, community-led services. But it is a lifeline – a sign that even as systems falter, communities remain determined to protect one another.

“There may be no funding,” Patriciah says, “but we are creative people… we will ensure everybody that needs a service is able to get it.” Baks (Y+ Kenya) says, “Once a peer educator, always a peer educator. We will support one another as young people.”

Nearly one year on from the cuts, Kenya’s HIV crisis already shows worrying signs of moving into the shadows – masked by the disappearance of prevention programmes, driven by people going underground, and dangerously shaped by the uncertainty of a system waiting for external support that may never return.

The country has not lost progress entirely. But it may be losing sight of where the epidemic is moving, and who is being left behind. Unless Kenya acts decisively to strengthen domestic financing, repair data systems, and restore safe, stigma-free spaces for key populations, the silent impact of the cuts may soon become far harder to control.

Tags

HIV preventionKenyakey populationsUS funding cuts