Six ways to stand against COVID-19 stigma: lessons from the HIV response

© Frontline AIDS/Gemma Taylor

© Frontline AIDS/Gemma Taylor

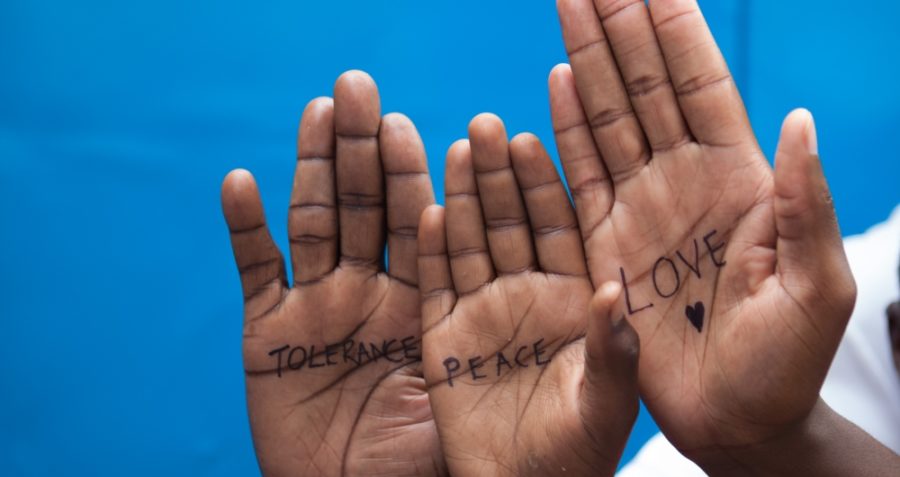

One of the enduring slogans from the HIV response is: Viruses don’t discriminate. People do.

This has a lot of currency in the COVID-19 crisis too. It recognises that some groups of people are more affected by the epidemic than others, but reminds us at the same time that we are all susceptible to catching the virus.

Stigma has huge power to undermine efforts to prevent and treat health conditions. The pervasive stigma experienced by people living with HIV can create an environment of fear and denial. Fear to test for HIV; denial of the possibility of being ‘at risk’; the desire to see the virus as ‘over there’, affecting others, not people ‘like me’. All of this makes people reluctant to protect themselves, to get tested and to seek treatment.

Stigma emerges quickly in times of crisis. To stave off the fear of disease, we cling to an identity of people ‘like me’ (who are not at risk, or affected) vs ‘others’ (who are). The ‘others’ are usually those already marginalised by existing social norms: stigma is gendered, homophobic, racist, ageist, ability-ist, and elitist.

But it is not inevitable. The HIV response tells us that, in addition to the hand-washing, the mask wearing, the staying at home and social-distancing, an important contribution we can make to the safety of ourselves and our communities in the time of COVID-19, is to stand against stigma. Here are six ways to do that.

1. Mind your language

Language is a powerful tool to create stigma – and also to stand against it. For HIV activists, the ‘Chinese virus’ of 2020 held haunting echoes of the ‘gay disease’ of the early 1980s. Since then we have seen the language around HIV change to become more sensitive and inclusive. We talk about people living with HIV (not ‘infected by HIV’, or ‘AIDS victims’); we talk about behaviours (men who have sex with men, people who use drugs) rather than potentially disparaging identities (‘gays’, ‘addicts’). In the COVID-19 response, we can modify our language to avoid unintentionally ‘othering’ those affected by the virus – instead of ‘victims’, say ‘people affected by COVID-19’. Instead of ‘infected’, say ‘affected’. Small adjustments in the language we use can have a big impact on reducing stigma and increase awareness of inadvertent use of stigmatising language.

2. Talk about safety, not war

Often, to preserve a sense of safety, we adopt a language of war. This is an extraordinary phenomenon, given that at no time are we in as much danger as in wartime. Yet the language of combat is often used when talking about illness, from cancer to COVID-19, whether in reference to an individual ‘battle’ or a global ‘war’ against a disease. This language risks associating people affected by the disease with the threat that must be fought off, increasing stigma and discrimination. The war language is in itself dipped in moral overtones, which suggest a weakness of spirit, or lack of moral fortitude, among those who ‘succumb’ to the virus, and fall ill or die. A good alternative is to talk about creating safety from, rather than fighting the pandemic. This can open up creative and innovative thinking and spaces for new opportunities beyond ending the epidemic – such as community-driven online safety campaigns and collaborative support systems.

3. Don’t blame yourself – or others

Overwhelmed with public health advice about hand washing and social distancing, we may be quick to assume that if we catch the virus, it’s our own fault. Or even worse, we might blame someone else for ‘giving’ it to us. But for many of us it’s not possible, or feasible, to live in such a way that we’re entirely without risk of COVID-19. The same goes for HIV, although the means of transmission is different (HIV only transmits via blood or bodily fluids). While doing what we can to protect ourselves and others, we must also acknowledge that our choices are often the result of a complicated process of weighing health concerns against financial, practical, emotional and social interests and relationships. Blaming ourselves, or others, for falling ill, or for ‘putting others at risk’ by being ill, is simplistic and unhelpful.

4. Talk about it

Silence breeds stigma. Talking openly about something will help normalise it, so it doesn’t become un uncomfortable topic we don’t talk about for fear of saying the wrong thing. Talk about your experiences, your fears, and your questions. Listen to other others’ with patience, interest, kindness and respect.

5. But don’t gossip

Don’t speculate about people’s health status, and don’t share someone’s personal health information with others. In many places across the world, lack of confidentiality among medical professionals as well as neighbours, friends and acquaintances remains a powerful disincentive to get tested for HIV and to seek treatment and care. Respect each other’s privacy. If someone wants their friends/neighbours/work colleagues to know they or people in their household have or had COVID-19, let them share it themselves.6. Counter misinformation.

6. Counter misinformation

Finally, rumour and misinformation feeds stigma, and undermines any rights-based public health response. Both the HIV and the COVID-19 responses have been set back by misinformation, sometimes even generated by the very individuals we should be looking to for leadership and guidance. Seek out and check information against evidence based, authorised sources, such as the World Health Organization (WHO) or national health authorities. Don’t be afraid to correct people if what they say is incorrect.

Tags

COVID-19Stigma and discrimination