Shattering the myths around ‘universal’ health coverage

As many countries move towards universal health coverage, Frontline AIDS executive director Christine Stegling and Aidsfonds director Mark Vermeulen reflect on the opportunities and challenges this approach poses for people at the margins of societies.

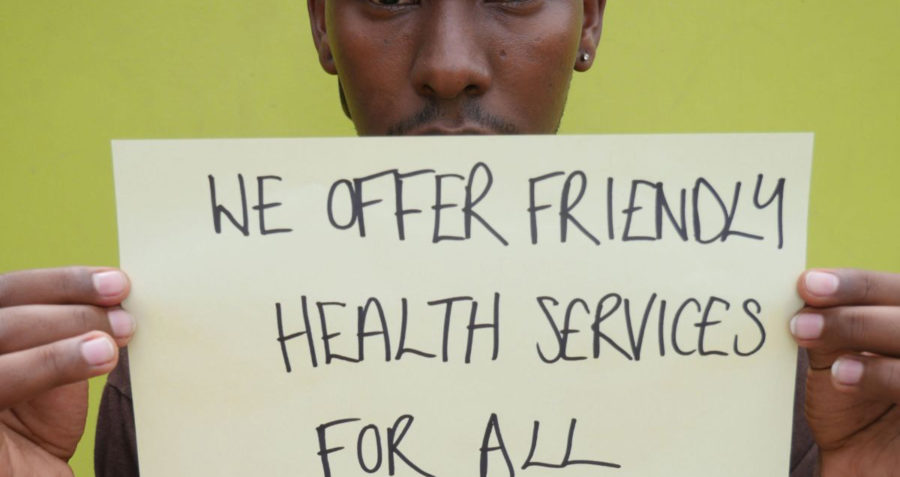

A world where universal health coverage (UHC) has been fully achieved would be a world where everyone, everywhere could access affordable, quality healthcare whenever they need it. This may sound aspirational but, recognising the centrality of good health to all our lives, leaders and policymakers included UHC as a specific target when agreeing the Sustainable Development Goals in 2015.

This intention is to be applauded and has been central to the arguments made by the HIV movement. Despite many victories, people who are criminalised and stigmatised – key populations such as men who have sex with men, people who use drugs, sex workers and lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender people – and are at higher risk of HIV or living with HIV, still face significant social and legal barriers when it comes to accessing health services.

As countries move towards implementing their versions of UHC, and as middle-income countries see decreases in donor support, there will be increasing pressure on health budgets, which we fear may lead to marginalised people being left behind once again.

When it comes to HIV, important decisions will have to be made in each country regarding which services will be continued and financed. We want to see HIV and sexual and reproductive health and rights included in every country’s UHC package, as recommended by the recent Guttmacher-Lancet report, and for countries to make these services available to their entire populations so that no one is excluded or left behind, especially those who are marginalised or criminalised.

New research conducted by Aidsfonds, Frontline AIDS and the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine in Indonesia, Kenya, Uganda and Ukraine reveals major areas of concern as countries move towards UHC, while at the same time transitioning from international to domestic funding for HIV programmes.

In each of these countries the decision on whether HIV services should be included in a national health insurance scheme is still to be determined. Just taking the issue of antiretroviral treatment (ART) alone, if access becomes contingent on being part of a national health insurance scheme, people who cannot afford to contribute may be denied life-saving treatment.

Indonesia and Kenya, which have already decided to introduce national contributory health insurances schemes, will keep some healthcare services with strong public health benefits, such as vaccinations, ‘free’ – meaning that people who are not able to regularly pay their contributions will still be entitled to these services. Providing ART is essential for preventing and managing HIV, yet the argument that it should be offered as a ‘free’ service is not yet won in either country. In Uganda there are plans to develop an AIDS Trust Fund financed by national and international sources to ensure HIV funding is protected. But needing insurance to access HIV treatment and other services has not yet been ruled out.

Discriminatory laws and policies may also stop HIV services being integrated into UHC. In Kenya, the government has signalled its interest in exploring the option that national or local authorities ‘hire’ civil society organisations to continue (and expand) the work they are currently doing. But the fact that some of these organisations work with and for people who are criminalised might create a serious obstacle: effectively, the government would be paying organisations to carry out activities that could be construed as supporting illegal behaviour. Similarly in Uganda, although the government supports continued working with NGOs to expand and deliver services, it is unclear how organistions working with men who have sex with men and LGBT people can continue their work when, under recently passed laws, they could be considered to be supporting illegal behaviour and therefore barred from registering as NGOs.

The study also suggests that civil society organisations that are currently able to influence national health agendas through HIV-related platforms may find themselves in a weaker position as countries move towards UHC. For example, in Indonesia civil society organisations have been included in the country’s National AIDS Commission and in local AIDS commissions since their inception. The National AIDS Commission was dissolved in 2017 and all its activities incorporated into the Ministry of Health, and meetings with civil society have become far more irregular. This has created the perception that civil society is no longer an equal partner when it comes to shaping the national health agenda.

For four decades, the HIV response has demonstrated the critical role that community and civil society organisations have played in advocacy, research, service delivery and in holding government to account, especially when it comes to the rights of the most vulnerable. This advocacy has led to improved access to HIV prevention, treatment and care, unprecedented mobilisation of international and domestic resources and, crucially, meaningful involvement of communities through the “nothing about us without us” principle.

We must now seize the moment to replicate this success on an even larger scale. By pushing for active involvement in UHC at a country level, civil society can bring the learnings of the past four decades of the HIV response to help shape a vision for rights-based, person-centred UHC that, if implemented, leaves no one behind. In Ukraine, the transformation of the government-run Centre for Combating AIDS into a public health centre shows what can be achieved. Community-based organisations working with the centre, that previously only worked on HIV and AIDS, are now expanding their scope. Through this transition process, close cooperation between government and civil society in providing services to marginalised people has become firmly rooted in Ukraine’s public health system.

Today, we stand at a crossroads of opportunities and challenges. By working with a range of partners, we can drive forward a positive vision for UHC that ensures that everyone has access to the services they need to live a healthy life, no matter who they are or where they live.

This research was conducted through the Partnership to Inspire, Transform and Connect the HIV response (PITCH), a strategic partnership between Aidsfonds, Frontline AIDS and the Dutch Ministry of Foreign Affairs.